Heritage watch brands: Longines celebrates 185 years of watchmaking

WOW takes a look at the storied relationship between the timekeeper and the early pioneers of aviation and navigation

The 2012 version of the Longines Avigation Type A-7 shares the same calibre as the current Type A-7 1935 version.

Welcome to a brand new year in watchmaking, which promises big things ahead. For this issue, we want to kick things off a little early. Yes, the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie is behind us and BaselWorld looms ahead, but we already know what one of the major highlights will be in 2017. It just so happens that this is Longines’ 185th anniversary and the Saint-Imier-based firm revealed in January that it has a programme and a menu in place for the festivities. This is an initiative that seeks to break down the momentous birthday into bite-sized chunks that you can savour every day. A sort of horological hors d’oeuvre, if you will.

Now, when you have a history like Longines’, tackling everything in one go is bound to result in a case of severe indigestion. After all, this is a brand that has a claim to fame in sports timing, in aviation, in travel and, by entirely natural circumstance, has a special relationship with the chronograph. Trying to make a meal of all these disparate courses is a recipe for disaster, so we commend the brand for pacing itself. In keeping with this spirit, our own stories about the brand will follow us throughout the course of the year, in every issue.

That said, we’ll leave behind the food metaphor for now because cuisine is one area Longines hasn’t quite conquered, although we will be happy to be proven wrong at BaselWorld! Seriously, our cover will clue you in on our focus this issue, but we’ll spell it out clearly here. This story looks at Longines’ significant depth in the area of pilot’s watches, and across aviation in general. We’ve chosen two pieces to take flight with: the Longines Avigation Type A-7 1935 (our cover star) and the Lindbergh Hour Angle.

Charles Lindbergh with his Spirit of St. Louis plane

For more information on the cover watch, take a look at our cover watch. For the purposes of this tale, however, our focus is on the broader association of Longines, the company, in the early 20th century with the pioneers of aviation. Properly speaking, Longines inked the first official pages of its aviation story in 1919, when the brand became the official supplier to the International Aeronautical Federation. It is this partnership that saw the brand developing precise and trustworthy professional instruments for aviators. The work of the company’s US director, the very noteworthy John P. V. Heinmuller was key here, as demonstrated in the example of the Lindbergh Hour Angle. More broadly speaking, Heinmuller got Longines involved with tracking and timing the flights of the aforementioned early aviation daredevils. At that time, just the act of getting into a plane and taking off took incredible courage.

The fact that this was happening in the United States was important, as the century of flight is most definitely an American one. For Longines, the strength of this association could even be felt in the post-WWII era, when one of its 1954 advertisements featured this tagline: “The price of travel is well worth the cost of a Longines.” Times have changed and today, we can even say that the value of time far exceeds the cost of travel.

The Angle of the Hours

The current version of the Lindbergh Hour Angle watch

If you put all the logos of watchmaking firms that claim a link to aviation and the history of global travel on a page like this one, things will get crowded in a hurry. Every firm with a history that preceded World War II likely has a story here but, over the years, legend often takes precedence over the facts. This is unfortunate because the facts are usually more interesting. Obviously, for the purposes of this story, we’re going to get into that most legendary of all pilot’s watches: the Lindbergh Hour Angle.

Now, 2017 also happens to be the 90th anniversary of Charles Lindbergh’s famous transatlantic flight from New York to Paris. It was May 21, 1927, when Lindbergh touched down at Le Bourget airfield, Paris, after a 33-and-a-half-hour flight in a high-winged Ryan monoplane called Spirit of St Louis. While this was suitably epic, its place in history is clouded over by legend, much like the Longines Hour Angle itself.

You might think Lindbergh is remembered to this day because he was the first person to cross the Atlantic Ocean in a plane, but he actually wasn’t; dozens of people had done it. Lindbergh’s fame rests on the fact that he managed his crossing solo and flew farther than any previous transatlantic attempts. He also opted to do so without a parachute and a radio, in favour of more fuel. Clearly, Lindbergh intended to give it his all, eschewing safety nets for an improved chance of success. As a result of this drive, presumably, he captured the imagination of the public. He was greeted at Le Bourget airfield by a crowd of at least 100,000, who had earlier caused the biggest traffic jam in Paris’ history because they were en route to greet him.

Longines chose wisely in having its trademarked logo be a winged hourglass, way back in 1905.

Somewhat fittingly, the varying accounts of the momentous event get a little confusing, leading to unsubstantiated reports that Lindbergh was wearing a Longines timepiece during the flight. While it might be that the stampede at the airfield, and Lindbergh’s later celebrity and association with Longines coloured the public’s perception of the historic flight, it is not even known if Lindbergh was wearing a watch when he landed. Whatever the case might be with regards to Lindbergh’s mystery travel companion, Longines’ own records indicate that it was indeed present for Lindbergh’s departure from New York and for his arrival at Le Bourget.

Drawing Up Plans

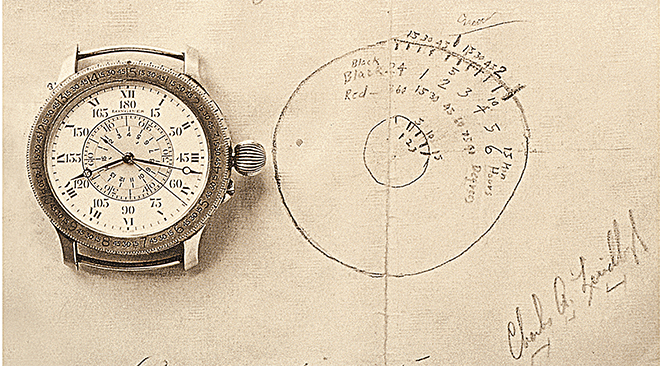

What we also definitely know is that the Lindbergh Hour Angle — possibly one of the most recognisable timepieces in the world — was designed by Lindbergh himself after his famous flight. Historian Michael Balfour records that Lindbergh made rough sketches of the dial, actually had these drawn up properly, and registered a patent for what is known today as the Lindbergh Hour Angle watch.

Balfour also goes on to note that Lindbergh brought his plans to none other than Heinmuller, president of the International Aeronautical Federation because the watch had a very specific usefulness for aviators. Lindbergh’s design allowed a pilot to accurately determine longitude by means of a graduated rotatable hour angle ring around the dial when used with a sextant and a nautical almanac. As fate would have it, Heinmuller was also in charge of the New York office of the Longines-Wittnauer Watch Company and he naturally brought the plans there. Obviously, Longines saw the merit in it and the firm’s records indicate that the Lindbergh Hour Angle watch was launched in 1931.

- Longines chose wisely in having its trademarked logo be a winged hourglass, way back in 1905.

- Calibre L699.2

Then, as now, the utility of the watch is narrow, targeting pilots alone, but the aesthetic appeal — powered in part by the impressive patrimony — is clear. Over the decades, the appeal has grown steadily even as the utility has fallen by the wayside; considering that entire generations have never used sextants and might not even know what they look like, much less how to use them. On the other hand, the meaning of the watch is, arguably, closer at hand than ever before.

Cosmos on your Watch

Ludwig Oechslin, former curator and director of the MIH (International Museum of Horology) at La Chaux-de-Fonds, once described the wristwatch as an expression of the cosmos on the wrist. Of course, he could have been referring to the materials used in the watch but not in this case. “With a watch, we can follow the rotation of our planet on a scale that is easy to grasp,” said Oeschlin. This is true of every watch, especially those with analog displays, but in the case of the Lindbergh Hour Angle, the wearer also gets to understand his or her own position on the planet. To illustrate this, we’ll chart it out in the next issue, when we hopefully will have seen a new Lindbergh Hour Angle watch at BaselWorld 2017.

The white dial here is in lacquer, while the original Type A-7 would have used porcelain

While this is truly a unique function in the world of watchmaking — the closest to it we know is the Weems watch, also from Longines that served as the base of the Lindbergh Hour Angle — it is the Lindbergh part of the name that defines the watch today. Apart from being a pioneering aviator, Lindbergh is perhaps even more widely known as the father in the infamous Lindbergh kidnapping case. This case also resonates today because the kidnapping of his son Charles Augustus Lindbergh directly resulted in the US making kidnapping a federal crime, as it remains today. While this tragic event doesn’t figure in the watch’s provenance, it did happen after the launch of the Lindbergh Hour Angle, in March 1932. It was certainly Lindbergh’s celebrity that drew the attention of the kidnapper and drove the public into frenzy for any and all scraps of news they could get.

Today, the triumph and the tragedy of Charles Lindbergh live on in the watch that bears his name.

Longines and the Chronograph

An individual named Alfred Lugrin (1858-1920) played an important role in the development of the chronograph on an industrial scale. It is no coincidence that Longines was known in the industry as a capable producer of chronographs as early as 1878. The reason for this is simple: Lugrin was one of the principal figures behind Lemania-Lugrin SA, which contemporary collectors know well as Lemania. Longines was the first firm to use Lugrin’s chronograph calibres on an industrial scale, having so great a success with these that it began making its own chronograph movements, possibly as early as 1910 (when the first patents appeared under Longines’ name).

- powers the Lindbergh Hour Angle watch

- The white dial here is in lacquer, while the original Type A-7 would have used porcelain

Longines’ provenance here is proven by the words of its peers, because who can you trust but your rivals? One Charles-Émile Tissot, watchmaker from Le Locle, declared at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair that Longines “exhibited a number of watches, plain movements and chronographs based on several special and patented calibres”.

The story of chronographs is one of vaunted suppliers, some of whom are but ghosts and legends today such as Venus and Landeron. In their heyday though, Longines was one of the few brands that demonstrated in-house mastery over the chronograph mechanism.

Today, the situation is quite different but oddly similar. Valjoux and Lemania are parts of ETA, which is owned by the Swatch Group. Obviously, this puts Longines in a fortuitous position because it too is part of the world’s largest maker of watches, allowing it to once again field exclusive chronograph calibres.

This article was published in WOW.