Guide: How to Successfully Invest in Art Part 3

We explore how to invest in art with passion, vision and a healthy dose of rational research.

In this third part of the series on truly investing in art with a blend of passion, vision and a healthy dose of rational research, the practical aspects of creating a lasting art collection come to the fore. Before I delve into these practical matters, a final thought after Singapore Art Week on the approach of successful art collectors.

Is there a common thread that binds these collectors; something that contributes to the lasting legacy of their connoisseurship? One factor that does stand out is the dedicated, deep research involved in the best collections. This combined with insatiable curiosity gives these collectors an enhanced ‘eye’. This level of in-depth research gives you an overview of an artist’s practice allowing you to select what you think is their best work. It requires a significant investment of time; an art advisor can be a useful asset in this regard. I take for granted my nerd-like love of detailed research. It was ingrained in me as a young trial lawyer regularly reading boxes of documents for ‘clues’ to help our story. Scientists and medics do the same. They read, review and consider vast amounts of material to burrow down into the answer or the better questions. This applies to art connoisseurship too.

Your collection expands beyond the wall space of your home – what next?

One clichéd definition of a collector is someone who has too much art to hang on their walls. If this is the case, where do you go from here? There are a range of exciting journeys your collection can embark on: collector’s groups; loans to art museums; exhibitions, books and online catalogues; a private museum or as collateral to invest in new works.

Private museums are increasingly becoming the destination for important art collections as the buying power of private collectors exceeds state-owned museums. Dallas’ Howard Rachofsky and Vernon Faulconer opened The Warehouse in 2013 to show their collections with a curatorial vision and an education department. Regionally, we have Dr Oei Hong Djien with three private museums in Indonesia to house his vast collection.

Other collectors loan or donate works to state museums. Uli Sigg, ground-breaking Swiss collector of Chinsese contemporary art, recently donated part of his collection to Hong Kong’s long awaited M+ Museum.

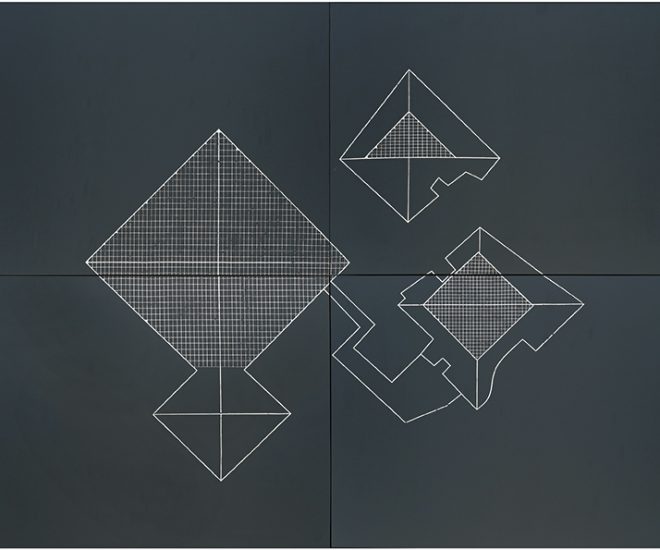

A private museum is a huge financial and time commitment. An alternative is to hold periodic exhibitions of parts of your collection, alone or with a group of like-minded collectors. Singapore has seen some wonderful examples. Mr Yeap Lam Yang worked with the ICA and Rogue Art to put together a thoughtful exhibition and book of landscape works from his collection; ‘Thinking of Landscapes’. This show demonstrates his personal journey as a collector. The show brought together Chinese ink works from Chen Ping and Yu Peng, Latiff Mohidin’s representations of his interior mind-scape and contemporary works by Michael Lee and Debbie Ding; the former using architectural plans of buildings left unbuilt to invoked fleeting memories of imagined or forgotten landscapes. A group of collector friends recently hosted ‘Alchemy’ at Artspace at Helutrans featuring important regional artists, Yee-I-Lan, Dinh Q Le, John Santos and international stars, Olafur Eliasson, Wolfgang Tillmans and Theaster Gates. It was an interesting opportunity to see these works together in Singapore.

Alchemy Installation View; Image courtesy of Alchemy.

The common thread amongst these forms of display are that you are also advocating for your artists. As a collector and connoisseur, part of the allure is to be able to support and share the vision of ‘your’ artists with others. Renowned collector of Chinese contemporary art, Uli Sigg, developed a collecting plan in the early 1990s and then relentlessly sought out curators in Europe to take an interest in the Chinese contemporary scene and visit the artists’ studios. The aim of his collection was to capture a moment in contemporary Chinese history; it is an embodiment of the zeitgeist at the time.

If much of your collection finds its way into storage, then an increasingly popular route is to use the collection as collateral. Modern art is more suited to this than contemporary art as the values are more stable. Specialized banks such as the Emigrant Fine Art Bank in New York are willing to loan against Modern Masters. This allows a collector to take advantage of the increased market value of a work without divesting it; and to open up possibilities of collecting new works. Typically, loans are offered on works over a fairly significant price point, say $500,000, with specialists viewing the work and the storage arrangements.

It almost sounds glib but it is very sound advice to buy the very best you can afford. Many passionate collectors will stretch themselves; Marc and Livia Straus started collecting in their 20s when Marc was at medical school. One of their early purchases was an Ellsworth Kelly which took them three years to pay off.

Divesting works from your collection

Whilst I would advise all collectors to buy works you wish to hold for life, sometimes your tastes change. We change throughout life and as you look back at your early purchases, you can trace your own personal history; one of the joys of collecting.

It is generally harder to divest well than to buy well. There are a number of routes to divest successfully including (i) returning the work to the gallery you bought it from, (ii) traditional auction houses, (iii) private sales or, (iv) online auction houses.

During your journey from art buyer to collector to connoisseur, it is important to build relationships with galleries directly or via your advisor. Galleries like to work with collectors who won’t flip the art (buy and quickly re-sell at a profit at public auction). When it is time to divest, your first port of call is the gallery you bought the work from. They may have a long waiting list of buyers for the artist and will want to ensure the work doesn’t appear at auction at a bad time. Many galleries explicitly guard against collectors re-selling work too quickly by including resale clauses on the invoice. These restrict the buyer from selling the work publicly for 3-5 years or giving the gallery right of first refusal.

If this avenue is not fruitful, the traditional auction houses such as Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Bonhams, Guardian, Poly Auctions were historically the way to sell art (usually a generation or so after it was bought). Before buying or selling anything at auction, I recommend attending an auction to experience the unique magic of the sale room and to see how prices can sky-rocket or works can fall flat.

Untitled (1982) by the street art-inspired Neo-Expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for $57 million at a Post-War and Contemporary Art sale at Christie’s New York recently. This price will include a buyer’s premium.

Auction houses charge commissions at both ends of the transaction to cover their hefty costs and exemplary marketing machine. Christie’s do not reveal their seller’s commission and offer a sliding scale dependent upon how keen they are to consign a sought-after work. However, it can be up to 10%. The seller may also be charged for marketing, restoration, shipping and handling. The buyer’s commission is listed on all of the auction house websites and is known as the buyer’s premium. Sotheby’s buyer’s premium is 25% on the first $200,000 of the hammer (sale) price. There is a sliding scale thereafter, with the premium moving down as the hammer price moves up. To help buyers understand the true price of a work during the bidding process, financial blogger Felix Salmon launched an app, GAVEL, to calculate the actual cost to the buyer. In some countries the buyer must also pay an Artist Resale Royalty (a right of the artist or his heirs to receive a fee on the resale of their works of art). The advantage of the big auction houses is the marketing effort they lavish on their big sales and their global reach.

The last 10 years have seen an explosion in online auction houses. The bigger players are US-based Paddle8 and Berlin-based Auctionata. Saffron Art in India has a blended offline and online model and recorded the highest price paid for an Indian sculpture ever. The advantage of the new online model is the lower commissions for both seller and buyer. New York based, Paddle8 has a buyer’s premium of 15%, a 10% saving on Sotheby’s.

A final consideration is a private sale. These may be organized by auction houses or galleries or private dealers. They will effectively aim to match-make a seller with a buyer via their network. This ensures your privacy and a lower commission.

If you like this article, check out parts one and two below:

How to Successfully Invest in Art Part One.

How to Successfully Invest in Art Part Two.

This story was first published in Art Republik.