Bridges and Ferrymen: An Exposition On “Dreams from the Golden Island”

‘Dreams from the Golden Island’ presents but a small fragment of what would be lost should the small voices from Muara Jambi remain unheard.

‘Dreams from the Golden Island’ is a publication by Jogjakarta-based writer Elisabeth Inandiak and Padmasana Foundation, a non-profit cultural advocacy organisation from Muara Jambi, a village on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. The book chronicles the story of this village, starting from the 7th century when it was at the crossroads of the Buddhist Sea Route between India and China. At its heart was a vast university complex, the largest in Southeast Asia which disappeared from historical records after the 13th century. Today, Muara Jambi is inhabited by a community of Muslim peoples, who are both the custodians of this archaeological site and the dreamers of this story.

An Exposition On “Dreams from the Golden Island”

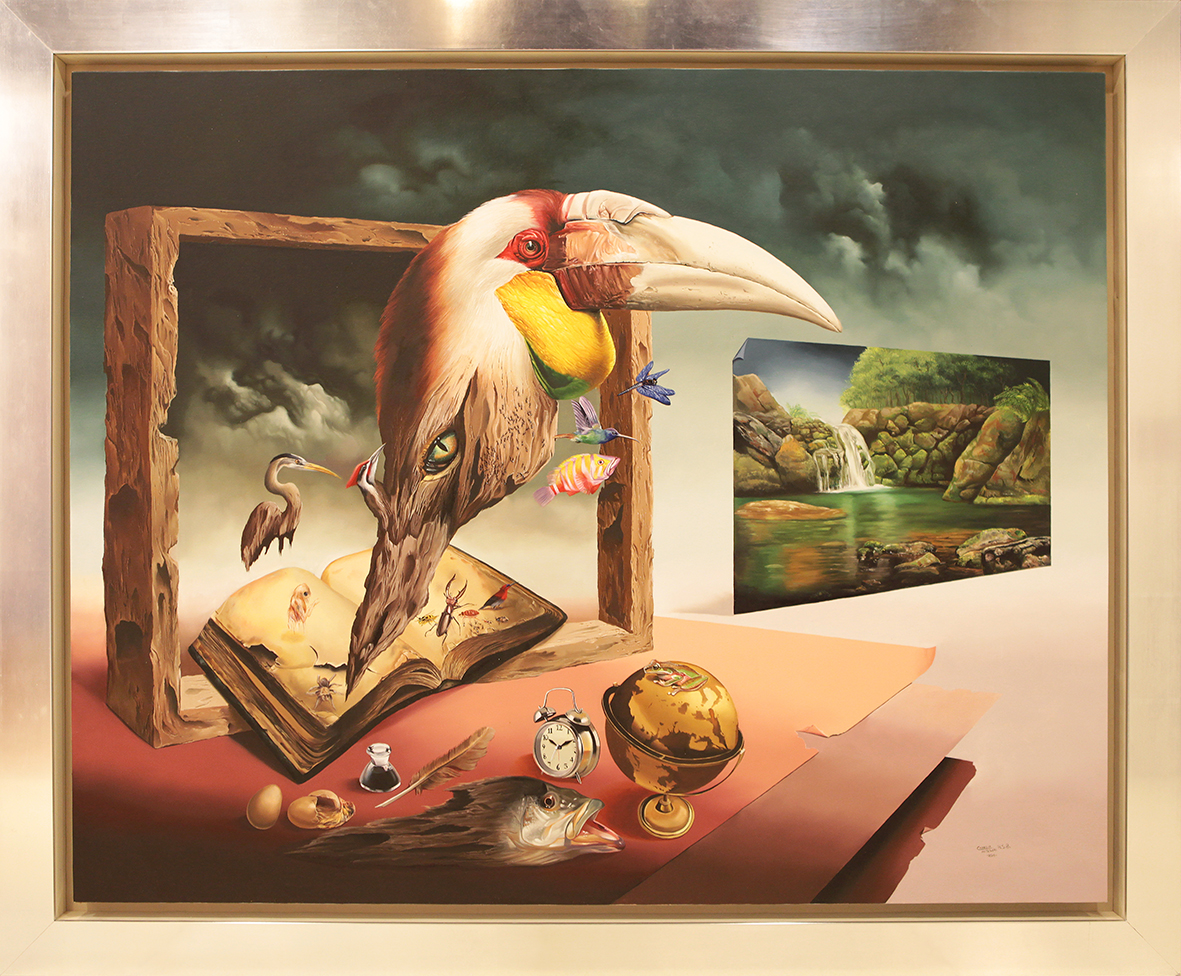

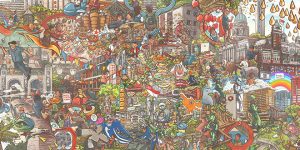

The book does not simply narrate a brief account of Sumatra’s pre- Islamic history but also provides insights about local customs practised today. It is richly illustrated with drawings by Pebrianto Putra, a young painter from the village, and features contributions by established contemporary artists such as Heri Dono, whose painting fronts the cover. The book also opens with a calligraphy by Singapore artist Tan Swie Hian, taken from ‘The Golden Light Sutra’. This text was translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the year 703 by I-Tsing, a Buddhist monk who made important sea journeys to Nalanda University in India in his quest for knowledge. A predecessor of I-Tsing who might be more familiar is Xuanzang, whose pilgrimage across the Silk Road-inspired the Chinese epic ‘Journey to the West’.

Indeed, these ancient travellers are not the only figures seeking and propagating knowledge. ‘Dreams from the Golden Island’ is written in an easily accessible manner, suitable even as a children’s book and translated into four languages: English, French, Bahasa Indonesia and Mandarin. Singapore author and poet Pan Cheng Lui contributed the book’s Mandarin translation and cited the importance of its content for Chinese Buddhists as impetus for participating in the project.

Two particular features of the book’s narration piqued my interest: one, it elucidates the ways in which art has connected peoples from disparate regions historically, and two, it functions as an advocate in contemporary times for environmental causes. The former is manifested most poignantly in a series of coloured images recounting the life of Atisha, an Indian sage who studied in Sumatra for 12 years and later brought the teachings to Tibet. What seems to be didactic illustrations are in fact Putra’s replica of murals found in Drepung Monastery — Tibet’s largest monastery — which is overlaid with calligraphy by Ven. Tenzin Dakpa. In 2012, Ven. Tenzin Dakpa visited Muara Jambi and was asked why he had to make the long journey from Tibet. He replied, “Since my childhood, I have studied the teachings and life of Atisha. I dreamed of this golden island as a fantasy island. And here I am. It was not a dream.”

As such, the gestures behind these images constitute a story told by the multiple hands involved. It reveals that Muara Jambi was a significant point of connection between Sumatra and Tibet because of their shared history and the movement of information. This is captured in the way these images are produced, which presents an otherwise impossible meeting of people across space and time. It is poetic how Atisha’s spirit found resonance in the arts, the one medium that could break boundaries of division commonly demarcated by differences in nationality, ethnicity and religion.

Here I quote Iman Kurnia, a member of the Padmasana Foundation who is responsible for the book design: “Art does not know limits. It is borderless because we unite as citizens of the world. Merging doesn’t mean we have to be the same, as difference generates strength, like a differential on the gearbox. The higher the differential, the more torque.”

As the book shifts from its chronicle of history into modern troubles, this is where Padmasana’s advocative message comes through. Beyond highlighting the historical significance of Muara Jambi, great emphasis is placed on the environmental threats it currently faces with the encroachment of industries in the area. In spite of its official status as a national heritage site, not much has been done to expel sand mining activity on the nearby Batanghari river. This has not only resulted in ecological devastation to the surrounding area but has also endangered artefacts on the river bed, which could themselves be precious archaeological clues that explain the mysterious disappearance of Muara Jambi’s ancient university. This lamentation is echoed in Mukhtar Hadi’s poem ‘Disaster on the Land of Melayu’, which was translated into a powerful performance presented on January 2018 at LASALLE’s Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore.

The waters of the Batanghari can no longer soothe the thirst Its currents that once ferried glorious tales. Today brought news of disaster to the Golden Island. The Prajnaparamita is petrified with shame. She would like to escape human rapacity Reduced to silence, she remains petrified. – Mukhtar Hadi (Borju), 2017

I end this exposition with a quaint watercolour drawing by Putra of Bukit Perak or Silver Hill, where a local legend tells of how the hill would lend silver plates to the villagers for their wedding banquets. Unfortunately, it stopped producing magic plates after the 1960s when some dishonest people failed to return the silverware. If this folklore is a cautionary tale about the relationship between human greed and the land, ‘Dreams from the Golden Island’ presents but a small fragment of what would be lost should the small voices from Muara Jambi remain unheard.