Eddy Susanto, Singapore Biennale 2016: Panji Tales

Images of the old relief ‘Panji’s Journey’ have been modified to align with Susanto’s imagination and artistic instincts based on research and fact.

Fact and fiction are common traits in the arts, and contemporary art is no exception. But to uncover hitherto unknown facts in a way that both reveals and fascinates is an art form in itself that only few artists command; one such artist is Eddy Susanto (b. 1975), who may be considered emerging but is in fact a seasoned artist.

At a time when many of his peers were trying to mimic popular trends in the international world of art, Susanto instead delved into historical readings to create and innovate with artworks that should come as eye-openers towards the place of Java in the global constellation of art and culture.

Entering the art world as an illustrator of hundreds of book covers locally and internationally, Susanto’s genius was further highlighted in 2011 when his version of the Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer’s ‘The Men’s Bath’ accorded him a prize in the prestigious Bandung Contemporary Art Awards. At first sight the painting appeared a real Dürer, but a closer view revealed the images were shaped by the letters of the Javanese script (called ‘hanacaraka’), which Susanto wrote with fine drawing pens, telling the story of a liberating spirit of enlightenment that came along with Islam in Java’s Northern ports. Susanto correlated the shift from the sacred order of the day’s rituals and ceremonies into productive industrial processes and income generating foci with the spirit of Renaissance in Europe, which changed its conventional culture and foci on the soul and after-life (memento mori) into a spirit of humanism that attached more importance to human rather than divine or supernatural matters, as revealed in Dürer’s works. Eddy Susanto then took Albrecht Dürer to represent that period of renewal in Europe, appropriating many of his works and outlining the contours of images with original texts written in Javanese script to represent a similar spirit prevailing in the respective Javanese narratives.

Amongst his noteworthy works is also his ‘500 years of Melenconia’ series, which he created to commemorate 500 years since Dürer created that artwork, recounting the situation under Maximilian I, King of the Romans, and his power over Europe that was marked by societal division expanding his territory through war and marriage. Europe had been split apart through political fragmentation, leading to despotism in several areas. Yet culturally, especially for Renaissance culture, they were polarised towards two, sometimes dichotomized, poles – North-South, however vague. A similar situation of societal structure prevailed in Java, as noted in ‘Babad Tanah Jawi’ (The History of Java), where rulers of the coast and hinterlands in Java also attempted to expand their lands through war and marriage. Similarly, 16th century Java had been fragmented into several powers, showing a dichotomised polarisation between the coast and the hinterland, referring to the same directions: North and South.

Eddy Sussanto, Java of Durer #02 (500 Years Melencolia I), 2014, Acrylic and drawing pen on canvas, 300cmx235cm

Finding similarities between diverse cultures in geographically diverse places and historically same or different periods of time has become Susanto’s trademark, making him a wanderer in art and culture whose art effectively highlights that what has been considered a feat of development of the West, was in fact commonplace in Java, long before.

His comparative artworks of websites, for instance, highlight the hyper contemporary JavaScript as a computer language in contemporary communication. Comparing the Javanese scripture with JavaScript, Susanto says both emerged as a medium of communication, each responding to the needs of the time. Susanto is of the opinion that the Javanese script could have become the computer programming language “if we had been smart enough” (a concealed critique to the lack of appreciation of one’s own cultural values). Such vision was expressed in the display of the works, with just a small device at the bottom displaying the colors and programs typical of such popular websites like Google, Yahoo, LinkedIn, Facebook or Baidu. From the tiny devices, melodious tones voiced by female singers ‘tembang sinden’ put the accent on the works.

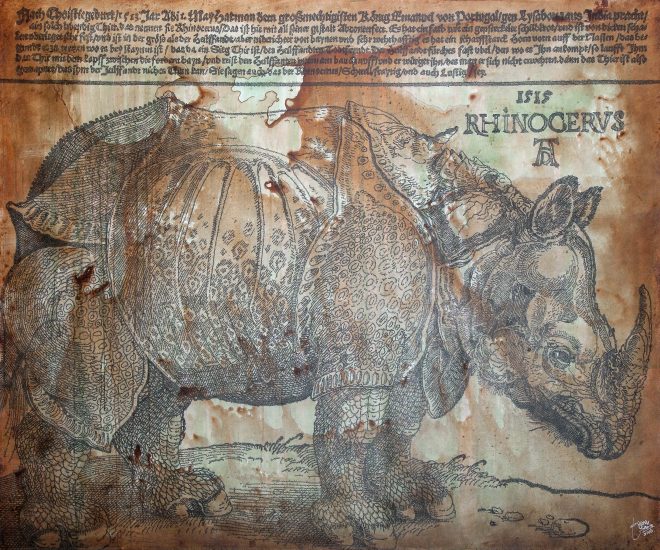

Another example of his inventive mind was the story of the rhinoceros that King Manuel of Portugal wanted to send as a gift to the Pope but suffered shipwreck on its way. It became an inspiration for his installation of ‘Badak Jawa’, the almost extinct rhinoceros from Java. Displayed with the body halfway inside the space, the rhinoceros sculpture of white resin was covered with Javanese script telling the story of shipwreck at a switch of UV lighting.

‘Badak Jawa’ Art Stage Jakarta edition in early August 2016 featured installations of plain white Rhino sculptures that, when illuminated by UV lighting, reveal rhinoceroses covered with Javanese script denoting related text from Babad Tanah Jawi. This was placed against seven engravings by Albrecht Dürer correlating with the spirit in stories occurring in Babad Tanah Jawi. With UV lighting, these images too underwent transformation, namely into images of Vasco Da Gama’s explorer ship carrying the letter to India in which King Manual of Portugal requests a live rhinoceros which he wished to send as a gift to the Pope in the Vatican, as he was seeking grace for his Eastern empire.

Dr Andonowati considers the number in Susanto’s ‘7 Java of Dürer’ of spiritual significance as it carries the notion of the esoteric in antiquity which is related to the divine. In Javanese cosmology, she says, this number has a sacred connotation: the Javanese world consists of seven layers consisting of three upper layers for the gods, three lower layers for the evil spirits, while the middle layer is the place of the human being.

Linking the same spirit of King Manuel in faraway Portugal of the 14th century to age-old Javanese cosmology, while combining Javanese script with materials of the present time (resin and UV lighting) reveals Susanto’s fascinating ability to unite the Zeitgeist (spirit of the time) of the Middle Ages with that of the present time.

But for the Singapore Biennale 2016, Susanto’s highlight of Java takes a bolder step, revealing an expansive treat of one of the most popular works in Indonesian literature which has travelled to the countries beyond Java by way of oral narration. Originating in Kediri in Eastern Java as a relief of 1400 A.D., the Panji story, which was written in the Javanese script, is now found in the countries known as Southeast Asia. Susanto’s work comes as an installation named ‘Panji’s Journey’. On an elongated canvas, the images of the old relief have been modified to align with Susanto’s imagination and artistic instincts based on research and facts. Leaning towards the semi-realistic Balinese style, the images are less stylised with the colors taking more vibrancy than in the Javanese style. The images are formed by pictograms corresponding to the Javanese alphabet. To indicate its origin, the canvas begins with Javanese script, then in the order of expansion follows the various scripts of the region where the episodes travelled – from Bali to Malaya, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Tagalog (Philippines) – heading towards the installation of the book ‘Wangbang Wideya’, with text in Latin by S.O. Robson, who bundled the Panji stories from the region, as well as symbolised Panji as the Lingua Franca of the region. The letters of several languages made of wood are attached to the canvas giving the impression they are falling down from the source and ending at the bottom with Latin letters, flowing over to touch the book of Panji stories in Southeast Asia compiled by S.O. Robson.

Tales of Panji, the legendary Prince of East Java, originates from Kediri where a relief from 1400 A.D. was found in the village of Gambyok in East Java. It was written in the local language using the Javanese script. According to the chronicles, the Panji tale travelled first to Bali, where it was preserved in the form of wayang beber (scrolls). It then travelled to the various lands of Nusantara, now popularly known as Southeast Asia, where 19 locations are still nurturing the cycle. Though mostly communicated orally, the Panji tale is considered an important literary heirloom, a literary classic of world class, authentic and complete with philosophical considerations emerging from the golden age of Majapahit, worth of its place as Memory of the World in the annals of UNESCO.

Susanto’s work clearly reveals his vision suggesting Java as center of the world, an awe inspiring response to the Singapore Biennale’s theme ‘An Atlas of Mirrors: From where we are, how do we picture the world – and ourselves.

Sngapore Biennale 2016 – Oct 27 to Feb 26

This article was first published in Art Republik.